From National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition

In March, NSAC teamed up with water quality, conservation, and grain and oilseed processor groups to encourage the USDA’s Farm Service Agency (FSA) to set aside at least a third of the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) acres for Continuous Conservation Reserve Program (CCRP) including the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) and the State Acres for Wildlife (SAFE) program.

This post provides some background and statistical analysis of these special initiatives to help provide more context for the recommendations contained in the recommendations to FSA contained in that letter.

Background in Brief

While no general sign-up for CRP has been scheduled for 2015, farmers and landowners do have ongoing opportunities to enroll acres within the continuous enrollment programs. The CCRP is a voluntary, non-competitive enrollment program that helps protect millions of acres of America’s most environmentally sensitive farmland. The CCRP targets specific blocks of land that are most vulnerable to erosion, key for preventing polluted runoff, and prime acres for wildlife habitat.

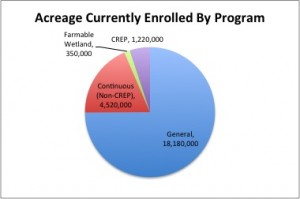

In the last five years, over 500,000 acres have been enrolled each year, and current contracts protect over six million acres reducing erosion, improving water quality, and restoring wildlife habitats.

As the name implies, enrollment in the CCRP happens on a continuous basis, and those determined eligible are automatically accepted into the program. This differs from the parent program, the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which features a competitive enrollment process with one general sign-up on an occasional basis.

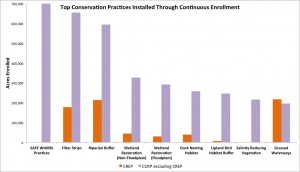

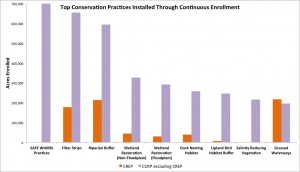

Within the CRP, conservation practices eligible for CCRP include riparian, wetland, and wildlife habitat buffers, filter strips, wetland restoration, grass waterways, shelterbelts, windbreaks, living snow fences, contour grass strips, salt tolerant vegetation, and shallow water areas for wildlife.

In exchange for removing environmentally sensitive land from production, CCRP contracts include an annual rental payment, certain incentive payments, and up to 50 percent cost-share to install the practice.

Regular CCRP Enrollments

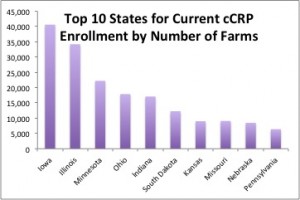

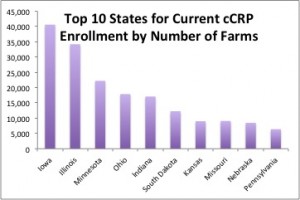

Currently, 4.52 million acres are currently enrolled in the mainstem of the CCRP program, with acres enrolled in all 50 states. Top users of the program include producers in Iowa, Minnesota, North and South Dakota, Illinois, Indiana, Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri. Despite the fact that 30 percent of enrollments by number of farm occur in the top two states (IA and IL), looking at each state by total CCRP acres, enrollment is spread fairly evenly across cropland in across the country.

Top Practices

Within the CCRP (including CREP and SAFE — see below), the most popular enhancements are installing riparian buffers and filter strips, creating permanent wildlife habitat, and restoring wetlands.

Farmers can protect the environment by placing small portions of their farms in permanent vegetation designed to control or intercept soil, nutrients, and pesticides and to slow wind and snow. Often referred to generically as conservation buffers, these targeted environmental practices can be in-field (e.g., contour grass strips), at the edge of fields (e.g., field borders), or along water bodies (e.g., riparian buffers). The best buffer strategies can remove 50 to 75 percent of nutrients and sediment from water bodies.

Buffers also provide food, cover, and shelter for some types of wildlife and also stabilize streams and reduce water temperature, benefiting fish and other aquatic species. And when used in conjunction with advanced farming practices like conservation tillage, cover cropping, crop rotation, and integrated pest management, buffer and related partial field vegetative practices help farmers become sustainable, environmentally and economically.

CCRP has been successful in targeting major erosion and water quality issues without sacrificing the productivity of entire fields. Because practices like Filter Strips make up smaller surface areas, these strategic enrollments have a disproportionately positive impact on stream health. In addition to controlling soil erosion, un-farmed strips of land give farmers access to parts of crop fields previously difficult to reach. Steep hillsides can also benefit from CCRP by installing contour buffers, grass waterways, and filter strips to help with drainage issues.

Ranchers benefit from using riparian buffers to protect from grazing along streams and ponds. Fencing cattle away from the buffer, installing alternative water sources, and planting trees the land adjacent to streams and ponds can help protect the land from erosion.

By enrolling their least productive soils, farmers can curb soil loss while attracting wildlife to their land and bring in additional economic benefits for the landowner. For areas that should never have been farmed to begin with, CCRP can be a useful tool to restore and land and return it back to its natural state.

Some conservation practices are more beneficial for particular regions, and as such are often concentrated in just a few states. For instance, Washington comprises 68 percent of the total acreage of contour grass strips in the US, while 90 percent of salinity reducing vegetation is in Montana and North Dakota and 64 percent of living snow fences are in Minnesota.

Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program

An offshoot of the CCRP is the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) under which a State agency and USDA together pay farmers to address targeted conservation issues identified by local, state, or tribal governments or non-governmental organizations. As a result of the added state funding, the average yearly rental payment per acre for CREP is $140, more than cCRP ($102), Farmable Wetland ($115), and General Signup ($51).

Top 10 states for CREP rental payments in dollars per acre

| Iowa |

$263.20 |

| Indiana |

$217.84 |

| Illinois |

$210.75 |

| Washington |

$194.37 |

| Ohio |

$192.95 |

| Kentucky |

$185.06 |

| Maryland |

$170.22 |

| New York |

$142.19 |

| New Jersey |

$136.96 |

| Idaho |

$132.77 |

CREP has been successful across the country to team up farmers and ranchers with state and federal efforts to address water quality and wildlife issues of concern at local, state, and regional levels.

▪ In Iowa, CREP is restoring wetlands to reduce nitrogen losses from the U.S. Corn Belt that cause hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico. These sites have nearly 2,000 acres of strategically enrolled wetlands plus buffer that are designed to reduce nitrate run-off from over 52,000 acres of tile-drained cropland.

▪ In Missouri, two cities sharing a water supply have gotten 175 area farmers to voluntarily enroll over 6,700 acres in order to protect the high-quality drinking water in their manmade reservoir. To date, this CREP project has resulted in an average 16 percent reduction in pesticide application in the Smithville Lake Watershed.

▪ The New York City Watershed CREP project partners New York farmers with the Watershed Ag Program to maintain and improve the drinking water quality for New York City. By investing $35 million to implement best management practices on 85 percent of the 400 farms in the 500,000-acre watershed, the city was able to avoid building a costly water filtration plant.

Wildlife and Wetlands

There are a number of program initiatives within the CCRP including upland bird habitat buffers, State Acres For Wildlife (SAFE), and pollinator habitat. These targeted initiatives have enhanced wildlife habitat on thousands of acres across the country.

For instance, in South Dakota, these programs have improved the landscape across the state allowing for ducks, pheasants, sharp-tailed grouse, wildflowers, and deer to return in greater abundance.

Top 5 states for cumulative acres enrolled into CCRP program initiative Upland Bird

Habitat Buffers

| IL |

64,805 |

| KS |

40,457 |

| MO |

29,340 |

| IA |

25,860 |

| OH |

15,676 |

Top 5 states for cumulative acres enrolled into CCRP program initiative State Acres for

Wildlife (SAFE)

| ID |

106,070 |

| ND |

101,777 |

| SD |

98,480 |

| TX |

87,638 |

| KS |

79,216 |

Top 5 states for cumulative acres enrolled into CCRP program initiative

Pollinator Habitat

| IA |

8,504 |

| IL |

8,066 |

| NE |

1,653 |

| CO |

1,305 |

| ID |

630 |

Practices eligible for the SAFE program in order of popularity include installation of grass, trees, wetlands, buffers, and long leaf pine. Idaho, Texas, and South Dakota are top recipients of SAFE contracts, allocating 117,300 acres to the improve habitat for the Columbian Sharp-Tailed Grouse, 122,700 acres for Mixed Grass, and 81,500 acres to for pheasant habitat, respectively.

Specific Wildlife Practices

In November 2014, USDA increased the SAFE acreage allocation by 100,000 acres to 1,350,000 acres. As of January 15, there are nearly one million acres enrolled in the SAFE practices, leaving about 350,000 acres yet to be enrolled. These programs will be open until allocations are reached.

Acres allocated and enrolled into SAFE practices

| Practice |

Acres Allocated |

Total Acres Enrolled |

% Enrolled Compared to Allocated |

| Flood-plain wetlands |

531,400 |

292,644 |

55 % |

| Bottomland hardwood trees |

250,000 |

112,883 |

45 % |

| Non-flood plain and playa wetlands |

418,600 |

327,139 |

78 % |

| Upland bird habitat buffers |

500,000 |

246,529 |

49 % |

| Longleaf pine plantings |

250,000 |

137,307 |

55 % |

| Duck nesting habitat |

300,000 |

258,186 |

86 % |

| State acres for wildlife enhancement (SAFE) |

1,350,000 |

972,195 |

72 % |

| Highly erodible lands |

750,000 |

244,086 |

33 % |

| Pollinator habitat |

100,000 |

22,823 |

23 % |

Conclusion

Since its inception, CCRP has been a vital tool for landowners to move a small, targeted portion of their land into various types of conservation buffers and habitat for extended periods of time in return for annual rental payments.

With over 6 million acres currently enrolled, USDA’s Farm Service Agency faces critical issues about how to manage the CCRP now that the 2014 Farm Bill has reduced the overall size of CRP in total. A key task will be ensuring sufficient acreage availability to maintain and grow the size of the CCRP over the coming five years to help address critical water quality and wildlife habitat issues.

Farmers and landowners face critical questions as well.

Those with land in the CCRP that is due to expire in the coming years face an important decision about whether to re-enroll for another decade.

Farmers and landowners with whole fields and farms in the regular CRP with contracts that are due to expire also face the question of whether to attempt to re-enroll or put the land back into production. For those choosing the latter course, an attractive option open to them is to keep buffer strips and targeted partial field practices in place through the CCRP while returning other portions of the farm to production. Choosing this option preserves important conservation values even as farms return to crop or livestock production.

Interested farmers and ranchers can learn more about the CCRP and how to apply in NSAC’s Grassroots Guide and can check out a variety of CCRP success stories on FSA’s website.