By Cynthia Palmer

American Bird Conservancy

A beekeeper grabs dead bees during a demonstration against the use of bee-killing pesticides

in front of the ministry in Sofia, Bulgaria, on April 22, 2013. Beekeepers gathered to protest

and to call for a moratorium on the use of neonicotinoid pesticides, which are hazardous to bees.

(Dimitar Dilkoff/AFP/Getty Images)

Rooted in gratitude for a good harvest, Thanksgiving is a day of togetherness and feasting for many Americans. It is a time to wipe the dust off Grandma’s delicious recipe cards or to head to the Deli Fresh grocery aisles for savory string beans and pumpkin pie. For many, Thanksgiving is the purest and most important holiday of all, unblemished by the commercialism that threatens to tarnish Christmas and other celebrations.

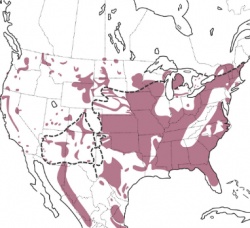

Behind the scenes, however, the cornucopia of foods for which we give thanks is now under siege, in part due to a new and insidious class of insecticides called neonicotinoids, or “neonics.” First introduced in the U.S. in 1994, the neonics quickly became the most widely used insecticides on Earth, applied to two-thirds of the world’s croplands. Virtually all the corn in this country is grown from neonic-coated seeds, as are many grains, fruits, and vegetables.

Unfortunately, these neonic insecticides are killing bees, butterflies, birds, and quite possibly bats and other wildlife. As such, they are a direct threat to our Thanksgiving meal, wiping out the tiny buzzing “field hands” that pollinate hundreds of crops—roughly one-third of the foods we eat. Pollinators play an essential role in our Thanksgiving celebrations—from the squash, sweet potatoes, broccoli, and other vegetables to the nuts, pumpkin desserts, apple pies, and cranberry sauce.

Even minute amounts of neonics are enough to kill the bees. The neonic coating on a single corn seed can kill over 80,000 bees. Bees that don’t succumb immediately face other effects: reduced memory and navigation, immune problems, developmental shortcomings, and diminished foraging ability. These impairments are as good as death to the parent colony.

Concerned about the impacts on bees, in 2013 American Bird Conservancy reviewed 200 studies, including 2,800 pages of industry research obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. Our assessment concludes that the neonics are lethal to birds as well. A single corn kernel coated with a neonic can kill a songbird. And as little as 1/10th of a coated seed per day during the egg-laying season can impair reproduction.

The ABC report also looks at aquatic insects, which are critical to avian aerial insectivores such as swifts, swallows, and nighthawks whose populations are now in decline. We conclude that the levels of these chemicals in our waterways are already high enough to kill the aquatic invertebrate life on which so many birds depend.

These findings are buttressed by the strikingly high levels of neonics found in a new review of surface water data from nine countries, and also by a recent study by Dutch researchers, published in the journal Nature, which noted that the higher the concentration of the pesticide in the surface water, the greater the decline in bird populations. A 2014 meta-analysis by the Task Force on Systemic Pesticides evaluates 800 peer-reviewed studies and confirms this spiral of unintended consequences.

Seed Tech Revolution

Neonics are part of a revolution in seed technology that has transformed American agriculture in recent years. Giant agribusiness companies including Monsanto, DuPont, and Syngenta control the commercial biotech market for seeds. They coat the seeds in neonics and embed them with genetically engineered (GE) traits such as immunity to Roundup herbicide, enabling farmers to use large amounts of weed-killers without harming their crops.

The companies maintain strict licensing agreements controlling the use of their coated, GE-impregnated seeds. For many crops such as corn and canola, it can be near impossible to find untreated seeds on the market. Attempts to clean and re-use seeds from prior years are landing farmers in court facing battalions of industry lawyers.

In encrusting our seeds in systemic insecticides, the chemical and seed conglomerates are transforming the way agriculture is done in this country. Neonic seed treatments are a pre-emptive strike; we are blanketing our lands with chemicals even when there is no pest to be found within 100 miles. This is a damaging reversal from integrated pest management, the approach to agriculture that says you monitor for pests, do all you can to prevent pest outbreaks, and apply conventional chemicals only as a last resort.

What is really quite extraordinary is that—despite the enormous scale on which they are used—there is scant evidence that neonics are actually increasing agricultural productivity. The EPA released its own analysis of soybean production on Oct. 16, concluding that “there is no increase in soybean yield using most neonicotinoid seed treatments when compared to using no pest control at all.”

The EPA review confirms what we have been telling the agency all year: that despite the enormous scale on which they are used, neonic seed coatings are not increasing agricultural yields. Scientific studies on corn, canola, and other crops show similar results, as documented by a recent Center for Food Safety assessment of independent peer-reviewed efficacy studies. The farmers pay for the costly treated seeds; the beekeepers bring home dead hives; and the birds, butterflies, and other wildlife die. The only benefit is to the handful of multinational biotech conglomerates, which accrue enormous profits.

Equally absurd is that, even though neonics are applied to hundreds of millions of acres in the U.S.—up to 95 percent of those lands via coated seeds—the EPA fails to require any registration of neonic seed treatments, or any enforcement in cases of misuse. EPA misinterprets its 1988 “treated article exemption,” 40 CFR § 152.25(a), to overlook the fundamental definition of a “treated article”: the pesticidal effects must not extend in significant ways beyond the article itself.

In the case of coated seeds, typically only 5 or 10 percent of the active ingredient is absorbed by the plant. The rest either blows away as dust during mechanized planting—killing the bees directly—or washes into the soil and ultimately the groundwater. EPA’s failure to require stringent testing and approval protocols for neonic seed coatings is a significant loophole, while its failure to track use and impacts helps perpetuate the myth that these chemicals can be used safely.

Birds don’t take a holiday and nor do bees. Their protection demands that we do away with policies that allow excessive use of ineffective and dangerous pesticides. Closer to home, as we prepare for our celebrations, let’s help save our pollinators by choosing carefully what we put in our shopping baskets and on our plates. We can help grow the market for sustainable, healthy, pesticide-free agriculture and help shrink the market for chemical intensive, neonic-contaminated products.

And as we give thanks for the bounty on our tables this Thanksgiving, let’s remember the birds and bees that made it all possible.

Cynthia Palmer is the director of pesticides science and regulation for the American Bird Conservancy in Washington, D.C.